The bleeding edge of Asia, the protruding Anatolian peninsula, breaks from the Fertile Crescent and juts out almost in desperation to the West, only non-consubstantial with what we define to be "Europe" by the Bosporus strait. At less than 20 miles long and narrower than a mile, this passage has been marked historically as the boundary between two worlds -- an immense cultural division imposed upon a minor geophysical feature. Yet the ancient peoples of this land shaped more than maps; they shaped humanity's very conception of boundaries, limits, and the definitions of existence itself.

To employ a popular modern term, this land of Anatolia is surely a liminal space, and such a space uniquely produced a people sensible to the precariousness of enacting definitions and boundaries upon the world. Within this land, a man known to history of Anaximander emerged in the year 610 BCE, in the city of Miletus. Following and going beyond the revolutionary conviction of his fellow Milesian, Thales, Anaximander endeavored to venture boldly into his material world and formulate a philosophical system in reflection of it. Quoting Nietzsche in Philosophy in the Tragic Age of the Greeks, Anaximander, as "the first philosophical author of the ancients" (as Thales is not known to have written anything), "sought to hear within himself the echoes of the world symphony and to re-project them..." In his ear, Anaximander heard not distinctive hi-notes or elaborate orchestral symphonies of individual expression. Rather, he discerned the tragic bassline of a boundless undifferentiated horizon, which by its own boundless depth produced and swallowed all fluctuations and pluralities again-and-again-and-again.

To stray from metaphoricals to metaphysics, this is just what Anaximander did! "He no longer distinguished a physical world from a metaphysical one, a realm of definite qualities from an undefinable 'indefinite.'" Anaximander naturally recoiled from the world of appearances and subjectivities, and this instinct revealed to him the warning of a greater, superior quality to the world of being beyond just that of physical manifestations or qualifications (this place is called what??, this plant grows where??, your name is huh??). In this vein, he was the West's first metaphysician. He regarded all being, or more specifically "all coming-to be{ings}" as "though {they} were an illegitimate emancipation from eternal being, a wrong for which destruction is the only penance." And in this, he became not just the West's first metaphysician, but also its first moralist --seeing all existence as a crime against the eternal -- and its first pessimist, recognizing that all things must pay the price of being by ceasing to be.

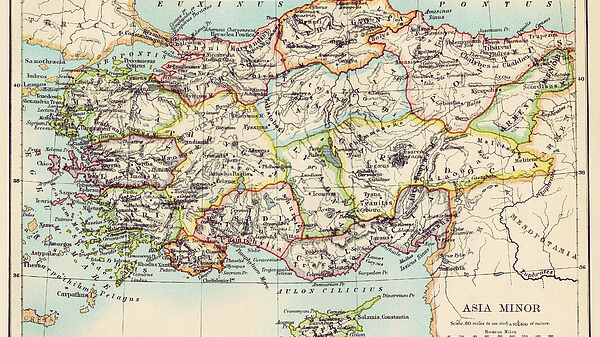

What material conditions would have shaped such a worldview? such a mind? such a negation? Anaximander's philosophical system (one may say, the first philosophical system) uniquely emerged as a product of the man's lived material and political existence within Miletus. In this time, no holistic entity known as "Greece" existed. Rather, distinct "Greek" peoples -- united by a shared language, a shared cosmogony (a la Hesiod), and a shared tragic oral tradition (a la Homer) -- lived in self-governing poli throughout much of the Mediterranean world. Beyond the mainland of Hellas (home to Athens, Sparta, Corinth), notable Greek satellite poli included Massalia (modern Marseille) and Neápolis (modern Naples). Greek peoples established these city-states as far off as the Crimean peninsula. Though connected by culture and maritime trading, Greek poli came about independently and often were extinguished independently, to be subsumed by barbarian peoples of mythic, unknown lands. Into a boundless horizon, the Greek city-states, the highest and most noble geopolitical productions of individual and cultural expression, dematerialized with the same violence and rapidity by which they emerged. Among these poli, Miletus existed in exceptional precariousness.

The image of a horizon remains most commonly associated with the sea, and Anaximander, from Miletus, witnessed daily the setting of the Sun from the Anatolian coastline onto the Aegean. From this horizon came trade and stories and Anaximander's own ancestors -- the qualified conditions which provided and historicized his defined particularities of reality. But the Sun rises in the East, and from the East likely came this concept's corollary in new and menacing manifestations of boundlessness, which uniquely spurred Anaximander's revelation and characterized it with a tragic gravity. Cities were falling, dynasties were collapsing, and Greek culture itself faced extinction from rising Eastern powers not distinguished by that Hellenic character for dynamic plurality and particularity but rather by totalitarian, divine-incarnate empires with boundaries much exceeding those of a Greek polis' city walls. In Anaximander's lifetime, Miletus faced the iminent threat of the Lydian Kingdom, with whom the Miletus warred between 600-585 BCE. The Lydians were not Greek, and their kingdom stretched far beyond what Milesians could imagine as a city-state's natural boundaries. Beyond the Lydians lay even vaster, incomprehensibly greater forces such as the Medes and the Babylonians, the latter of whose cyclical conceptions of empires rising and falling certainly having reached the Milesians and Anaximander. From Miletus' hazardous vantage, a sharply Greek originality and self-sovereignty confronted the impending forces of annihilation to produce within Anaximander his arche, or first principle, of the apeiron -- "that which has no boundaries."

In reference to Anaximander, Aristotle defines -- in his Physics -- how "the infinite body will obviously prevail over and annihilate the finite body." In wake of this inevitability, Anaximander embedded a moral quality to the idea of being (definitive particularity) and non-being (undefined boundlessness), viewing self-differentiated matter's destiny for obliteration and subsummation as an indicator of a hubris against nature. Anaximander says himself: "Where the source of things is, to that place they must also pass away. according to necessity, for they must pay penance and be judged for their injustices. in accordance with the ordinance of time." To reinvoke Nietzsche: "Wherever definite qualities are perceivable, we can prophesy, upon the basis of enormously extensive experience. the passing away of these qualities. Never, in other words, can a being which possesses definite qualities or consists of such be the origin or first principle of things." For Anaximander, Greek city-states, as self-governing, distinctive entities which popped up all over the Mediterranean shouting "Here I Am!! I am this person, I am this city, and these are my boundaries!" transgressed against the only real force of this world, the apeiron, the boundless. Of the supposed boundaries and definitions which the Greek claims, the apeiron views as simply local phenomena, like a local maximum value of a mathematical function which asserts superiority despite the actual range ascending to infinity (or perhaps, as would be Anaximander's view, towards undifferentiation).

Thus, understanding the material inputs of Anaximander's time serves towards establishing a genealogy of his philosophic output. He came to understand the inevitability that Miletus, a small, pugnacious city, would simply -- despite its singular vigor and distinctive cultural output, as was so common and admirable of the Greek city-states -- cease to exist. Boundaries mean nothing to the boundless. And the man was right. Shortly after his death, the boundless East would arrive in its final form, as the Lydian local maximum threat became subsumed into the newly-formed Persian Empire under Cyrus the Great. In quick succession, all of Ionia fell under Persian rule. The bounded sovereignty of Miletus evaporated. History progressed, and Miletus passed hands from Persians to the Athenians (in their imperial manifestation), then to Alexander the Great (the apeiron incarnate) and then to the Romans and on-and-on. Never again would Miletus' city walls mean anything, other than as ruins symbolic of an age of hubris -- men who sought to defy reality itself and create within it the a fable of individual Miletus assertions against a cold boundless infinite.